Eurasian watermilfoil was first detected July 2024.

No other invasive species have been identified in Friends Lake! Let’s fight to keep it that way

Take the necessary precautions to prevent the contamination of our lake and the spread of invasive species. Make sure your family, friends, guests and renters are educated! Put information on invasives with your rental materials, including Best Practices for Water Quality. FLPOA is proactive in its water testing. In addition, as a result of our extensive advocacy, the Town of Chester government created a special taxing district as a revenue source to be used in addressing the control and, hopefully, the elimination of an invasive aquatic plant infestation, if the situation becomes warranted.

To protect the lake and the environment, educate yourself on potential environmental hazards and invasive species and methods of prevention. Highlighted below are some major environmental concerns to be aware of. For more information, see the official report by New York State on aquatic invasive species or download the Aquatic Nuisance Species Handbook (PDF) or the Aquatic Nuisance Species Handbook from Michigan State.

We provide information on Invasive Species generally known in our area for your education. Some of these specifies are listed below:

| Plants | Animals | Animals |

|---|---|---|

| Curly Leaf Pondweed Eurasian Watermilfoil European Frog-bit Fanwort Hydrilla Starry Stonewort Variable-leaf Watermilfoil European Water Chestnut | Asian Clam Chinese Mystery Snail Fishhook Water Flea Quagga Mussel Round Goby Rusty Crayfish Spiny Water Flea Zebra Mussel | Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Emerald Ash Borer Spotted Lanternfly |

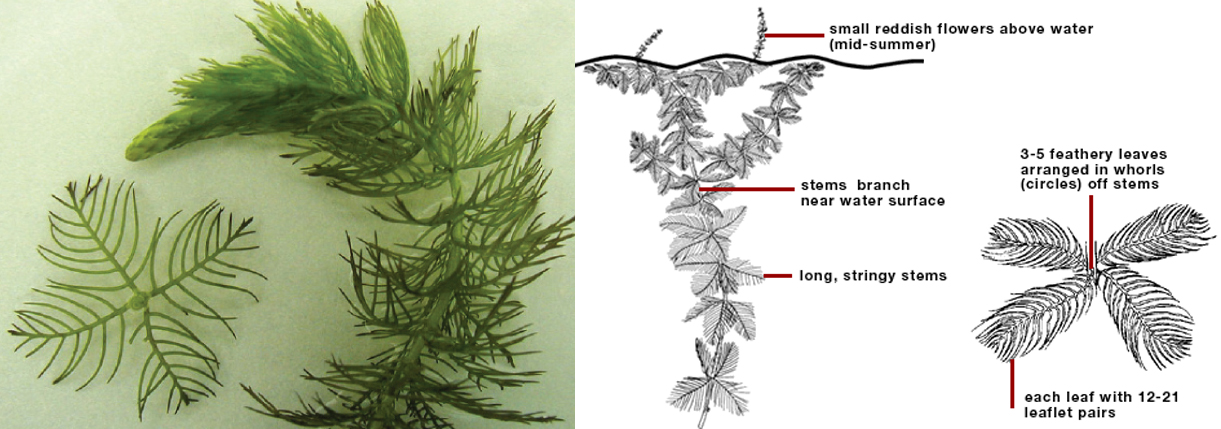

Eurasian Watermilfoil

Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) is one of the greatest threats our lake faces in the Adirondacks! You can download and print this identification card to keep in your boat or in with your rental materials.

It is native to Europe, Asia, and north Africa. It is a submerged aquatic plant, and grows in still or slow-moving water, and an invasive species in North America.

Identification

Eurasian watermilfoil has slender stems up to 3 m long. The submerged leaves (usually between 15–35 mm long) are borne in pinnate whorls of four, with numerous thread-like leaflets roughly 4–13 mm long. Plants are monoecious with flowers produced in the leaf axils (male above, female below) on a spike 5–15 cm long held vertically above the water surface, each flower inconspicuous, orange-red, 4–6 mm long. Eurasian water milfoil has 12- 21 pairs of leaflets while northern watermilfoil M. sibiricum only has 5–9 pairs. The two can hybridize and the resulting hybrid plants can cause taxonomic confusion as leaf characters are intermediate and can overlap with parent species.

In lakes or other aquatic areas, the Eurasian plant can quickly spread. In lakes it can form thick underwater stands of tangled stems and vast mats of vegetation at the water’s surface. In shallow areas the plant interferes with water recreation such as boating, fishing, and swimming. The plant’s floating canopy can also crowd out important native water plants.

How it spreads

Milfoil may become entangled in boat propellers, or may attach to keels and rudders of sailboat. Stems can become lodged among any watercraft apparatus or sports equipment that moves through the water, especially boat trailers. Eurasian watermilfoil can grow from broken off stems which increases the rate in which the plant can spread and grow. A single segment of stem and leaves can take root and form a new colony. Fragments clinging to boats and trailers can spread the plant from lake to lake. The mechanical clearing of aquatic plants for beaches, docks, and landings creates thousands of new stem fragments. Removing native vegetation creates perfect habitat for invading Eurasian watermilfoil.

Prevention & Control

Since roughly the year 2000, hand-harvesting of invasive milfoils has shown much success as a management technique. Several organizations in the New England states have undertaken costly, large scale, lake-wide hand-harvesting management programs with extremely successful results. Acknowledgment had to be made that it is impossible to completely eradicate the species once it is established. As a result, maintenance must be done once an infestation has been reduced to afford-ably controlled levels. Well trained divers with proper techniques have been able to effectively control and then maintain many lakes, especially in the Adirondack Park in Northern New York where chemicals, mechanical harvesters, and other disruptive and largely unsuccessful management techniques are banned. After only three years of hand harvesting in Saranac Lake the program was able to reduce the amount harvested from over 18 tons to just 800 pounds per year.

The European Water Chestnut

(Trapa natans) is native to Europe, Asia and Africa. In its native habitat, the plant is kept in check by native insect parasites. These insects are not present in North America and the plant, once released into the wild, is free to reproduce rapidly. Trapa colonizes shallow (less than 16 feet deep) areas of freshwater lakes and ponds, and slow-moving streams and rivers, where it forms dense mats of floating vegetation.

Identification

The European water chestnut is a rooted aquatic plant with submersed and floating leaves. The feathery submersed leaves form whorls around the stem; the 3/4 to 1 ½ inch glossy green floating leaves are triangular with toothed edges and form rosettes around the end of the stem. Single small, white flowers with four 1/3-inch long petals sprout in the center of the rosette. The plant’s cord-like stems are spongy and buoyant and can reach lengths of up to 16 feet (although typical lengths tend to be in the six to eight foot range). The stems are anchored to the bed of the waterbody by numerous branched roots.

Impacts

European water chestnut has become a significant nuisance throughout much of its range, particularly in the Hudson, Connecticut and Potomac Rivers, and in Lake Champlain. The plant can form nearly impenetrable floating mats of vegetation. These mats create a hazard for boaters and other water recreators. The density of the mats can severely limit light penetration into the water and reduce or eliminate the growth of native aquatic plants beneath the canopy. The reduced plant growth combined with the decomposition of the European water chestnut plants which die back each year can result in reduced levels of dissolved oxygen in the water, impact other aquatic organisms, and potentially lead to fish kills. Trapa’s rapid and abundant growth can also out-compete native aquatic vegetation. The European water chestnut has little nutritional or habitat value to fish or waterfowl and can have a significant impact on the use of an infested area by native species. The sharp, spiny nuts can result in puncture injuries to swimmers and people walking along the shore of infested areas. Because of its invasiveness and the severity of its impacts, the species has been listed under the federal regulations that prohibit the interstate sale and transportation of noxious plants.

Control

It is much easier (and less expensive) to control newly introduced populations of European water chestnut. Therefore, early detection and a rapid response are the key to preventing substantial, high-impact infestations. Small populations of European water chestnut, found in the early stages of colonization, can be controlled by hand pulling by volunteers in canoes or kayaks. Kayaks are more maneuverable and can be used in shallower water; canoes can carry more vegetation. Large infestations usually require the use of mechanical harvesters or the application of aquatic herbicides. Mechanical harvesting can remove the thick mats of vegetation in situations where boating and angling are negatively impacted. However, this is just a temporary measure as the plants will grow back the next season from seeds on the bed of the waterbody. Long-term treatment (mechanical or chemical) can be very expensive. From 1982 through 2001, the states of New York and Vermont spent more than $4.3 million on Trapa control measures on Lake Champlain.

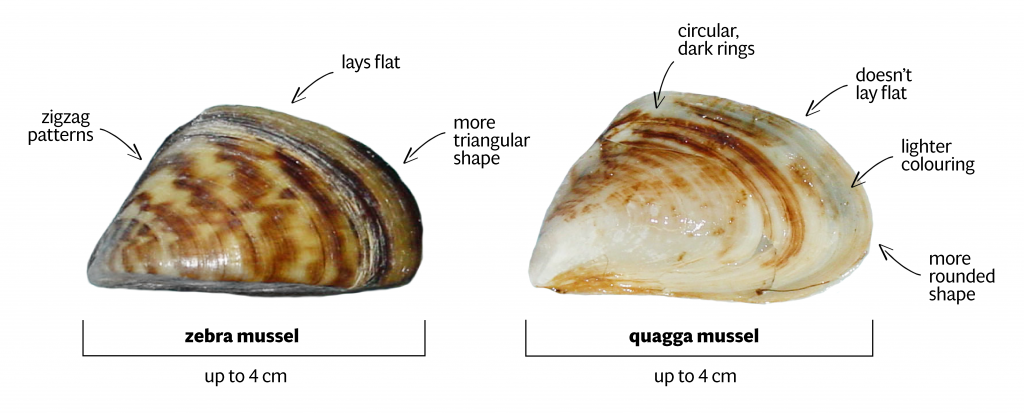

Zebra Mussels

Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) is a small freshwater mussel. This species was originally native to the lakes of southern Russia, has been accidentally introduced in many other areas and become an invasive species in many different countries worldwide, including the Adirondacks.

Zebra mussels get their name from a striped pattern which is commonly seen on their shells, though it is not universally present. They are usually about the size of a fingernail, but can grow to a maximum length of nearly 2 in (5.1 cm). Shells are D-shaped, and attached to the substrate with strong byssal threads, which come out of their umbo on the dorsal (hinged) side.

Impact

Zebra mussels have become an invasive species in North America, Great Britain, Ireland, Italy, Spain, and Sweden. They disrupt the ecosystems by monotypic colonization, and damage harbors and waterways, ships and boats, and water treatment and power plants. Water treatment plants are most affected because the water intakes bring the microscopic free-swimming larvae directly into the facilities. The Zebra Mussels also cling on to pipes under the water and clog them. It has been argued that Zebra Mussels also have had an effect on fish populations, with dwindling fish populations in areas such as the infested Salford Quays.

Zebra mussels are filter feeders. When in the water, they open their shells to admit detritus. As their shells are very sharp, they are known for cutting people’s feet, resulting in the need to wear water shoes wherever they are prevalent.

Since their colonization of the Great Lakes, they have covered the undersides of docks, boats, and anchors. They have also spread into streams and rivers nationwide. In some areas they completely cover the substrate, sometimes covering other freshwater mussels. They can grow so densely that they block pipelines, clogging water intakes of municipal water supplies and hydroelectric companies.

Zebra mussels are believed to be the source of deadly avian botulism poisoning that has killed tens of thousands of birds in the Great Lakes since the late 1990s. Because they are so efficient at filtering water, they tend to accumulate pollutants and toxins. Although they are edible, for this reason most experts recommend against consuming zebra mussels.

They are also responsible for the near extinction of many species in the Great Lake system by out-competing native species for food and by growing on top of and suffocating the native clams and mussels.

Control

Since zebra mussels damage water intakes and other infrastructure, methods such as adding oxidants, flocculants, heat, dewatering, mechanical removal, and pipe coatings are becoming increasingly common.

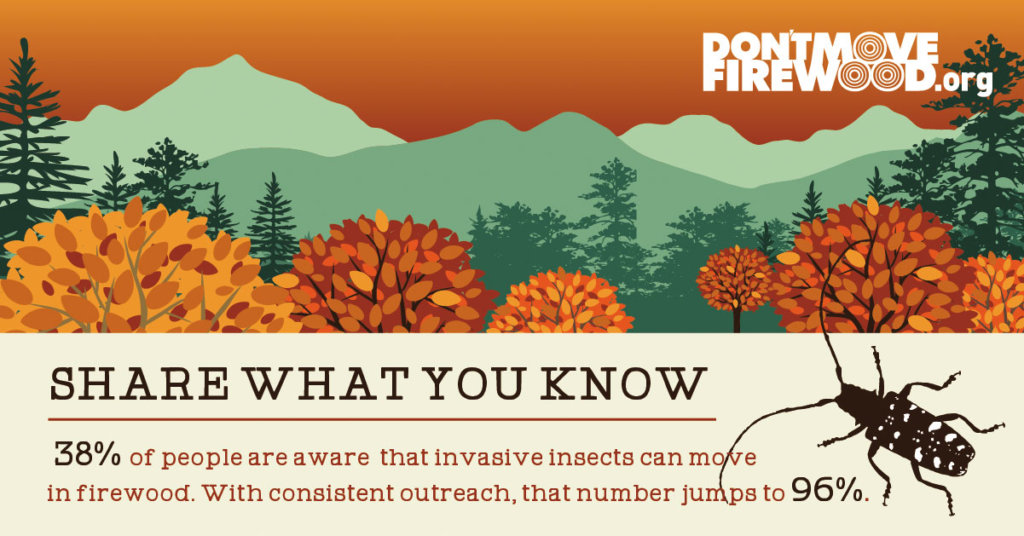

Firewood Regulations – Don’t Move Firewood

Please remember that there is a NYS Department of Environmental Conservation regulation that prohibits the movement of untreated firewood more than 50 miles from its source. The regulation also prohibits the importation of firewood into New York unless it has been treated to kill pests.

Learn more from Don’t Move Firewood.org